- HOME

- Research

Research

Research Overview

At the Department of Anatomy, Kumamoto University, we place particular emphasis on the question of how organs and tissues acquire their final form—that is, “how they are built” and “what developmental history they carry.” Our research is grounded in this anatomical and developmental perspective.

By combining this viewpoint with cutting-edge experimental techniques and interdisciplinary approaches from engineering and the semiconductor field, we aim to unravel the organ-specific structural “signatures” and “records” that underlie development and disease. Our goal is to establish a research platform that can generate new insights into disease mechanisms and provide clues for novel therapies and drug discovery.

While our core expertise lies in the cardiovascular field, our appointment within an anatomy department has allowed us to expand our research from the heart and vasculature to all organs and a broad spectrum of diseases. We are thus working toward a cross-organ, cross-disease understanding of pathology based on structure and developmental history.

The laboratory is led by Dr. Yuichiro Arima, who trained as a cardiologist (cardiovascular internal medicine) at Kumamoto University before taking up his current position in the Department of Anatomy. Building on this distinctive yet coherent career path, we seek to reinterpret the background of various diseases in different organs through the lens of developmental biology and anatomy, starting from a strong foundation in cardiovascular medicine and clinical experience.

Research Projects

1. Structural Links Between Cardiovascular Development and Adult Disease

Structures and tissue networks formed during development may no longer be visible in the adult body. However, their traces and design characteristics—reflecting the “developmental individuality” of each organ—can remain embedded within organs and influence disease susceptibility, progression, and responses to treatment.

The heart is an especially complex organ, shaped by the interplay of multiple cell populations. We have shown that, during the formation of the coronary arteries (the vessels that nourish the heart), a cell population that would normally contribute to cranial and skeletal structures also gives rise to coronary artery smooth muscle cells. We named this population preotic neural crest cells and reported their contribution to coronary artery smooth muscle through endothelin signaling. Notably, the region where these cells are distributed corresponds to areas prone to calcification in adult vascular disease, suggesting a significant link between development and later pathology.

Ref: Preotic neural crest cells contribute to coronary artery smooth muscle involving endothelin signalling, Nature Communications (2012)

We also approach developmental history from the standpoint of non-destructive, three-dimensional structural analysis. In collaboration with the Faculty of Engineering at Kumamoto University, we have established a micro–X-ray computed tomography (micro-CT)-based method to visualize and quantitatively compare the entire vasculature of the mouse hindlimb. Using this technique, we demonstrated that transient embryonic vessels—normally regressed during development—may serve as candidate sources for collateral circulation (alternative vascular pathways) when blood flow in the limb becomes compromised (ischemia).

Ref: Evaluation of Collateral Source Characteristics With 3-Dimensional Analysis Using Micro–X-Ray Computed Tomography, Journal of the American Heart Association (2018)

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/jaha.117.007800

This developmental, evolutionary, and structural perspective is not limited to cardiovascular disease. We are extending this conceptual framework to the understanding of diverse conditions, including cancer, chronic inflammation, immune disorders, respiratory and neurological diseases, and metabolic disorders, by revisiting their “design principles” from the standpoint of organ architecture and developmental history.

2. Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) Project

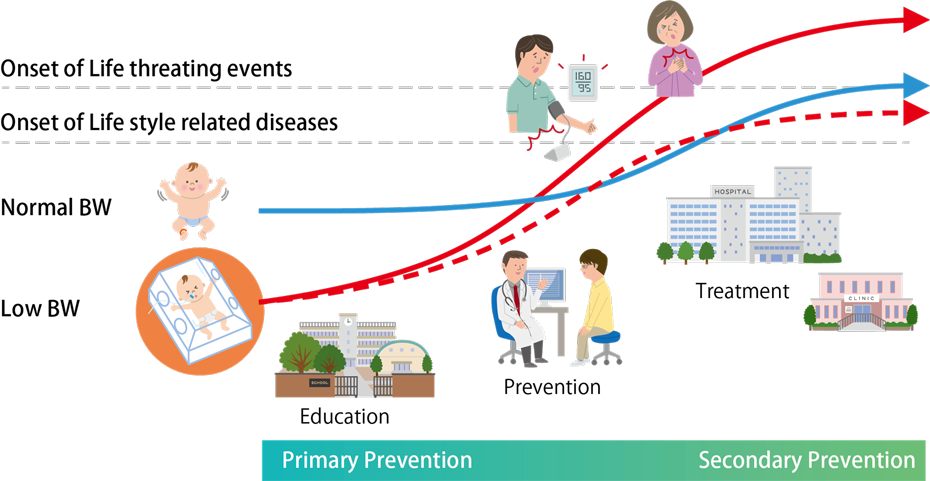

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis posits that environmental factors during fetal life and the early postnatal period influence disease risk and organ vulnerability later in life. Epidemiological studies have shown, for example, that individuals born with low birth weight are at higher risk of cardiovascular disease in adulthood. However, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, and robust preventive and therapeutic strategies have yet to be fully established.

In our department, we use the framework of organ developmental responses in the cardiovascular system as a starting point to expand DOHaD research to many organs and disease entities. Our aim is to understand how developmental stress affects organ formation and function across the entire body in an integrated manner.

We also place particular emphasis on biological changes that occur during transition phases (critical life stages), such as the perinatal period, maturation, and aging. We believe that understanding how organs respond structurally and functionally during these transitions is essential for realizing a healthy, long-lived society and advancing preventive medicine.

In the course of investigating the effects of ketone body metabolism, we have used mouse and rat models lacking a key enzyme required for ketone body synthesis. These studies revealed that the process of ketone body synthesis itself can help preserve mitochondrial function by preventing excessive accumulation of acetyl-CoA and subsequent protein hyperacetylation. This work has provided new insights into how neonatal metabolic states may influence organ development and the later-life risk of adult-onset diseases.

Ref: Murine neonatal ketogenesis preserves mitochondrial energetics by preventing protein hyperacetylation, Nature Metabolism (2021)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s42255-021-00342-6

Currently, we are applying optical and inducible technologies to develop animal models in which we can directly examine the timing and switches of organ-forming responses to developmental stress. Through these efforts, and within a framework of strong medical–engineering collaboration, we aim to build a robust experimental foundation for DOHaD research.

3. Integration of Medicine, Engineering, and Semiconductor Technology

To understand disease and develop new therapeutic strategies, it is not sufficient to study only genes and molecules; we must also quantitatively evaluate actual structural changes in organs and tissues. For this reason, we place great importance on establishing a framework for non-destructive, three-dimensional, quantitative phenotyping that allows direct comparison of morphological changes across organs and disease models.

In our department, we value the “anatomical eye”—the trained capacity to observe structure—as a starting point for research. Building on this observation-based perspective, we are developing research that extends across organs and diseases. By combining high-resolution imaging, optimized imaging protocols tailored to each organ, optical engineering techniques, and biosensing technologies, we aim to create an integrative platform that captures aspects of disease that conventional approaches in medicine and life sciences alone cannot easily reach.

These efforts rely on the strengths of Kumamoto University as a comprehensive university that promotes interdisciplinary research. In particular, we are strengthening collaborations with the Faculty of Engineering and the semiconductor-related research community to build a research infrastructure that can be applied to non-destructive anatomical evaluation of diverse disease phenotypes, including cardiovascular, metabolic, immune, respiratory, neurological, and oncological disorders.